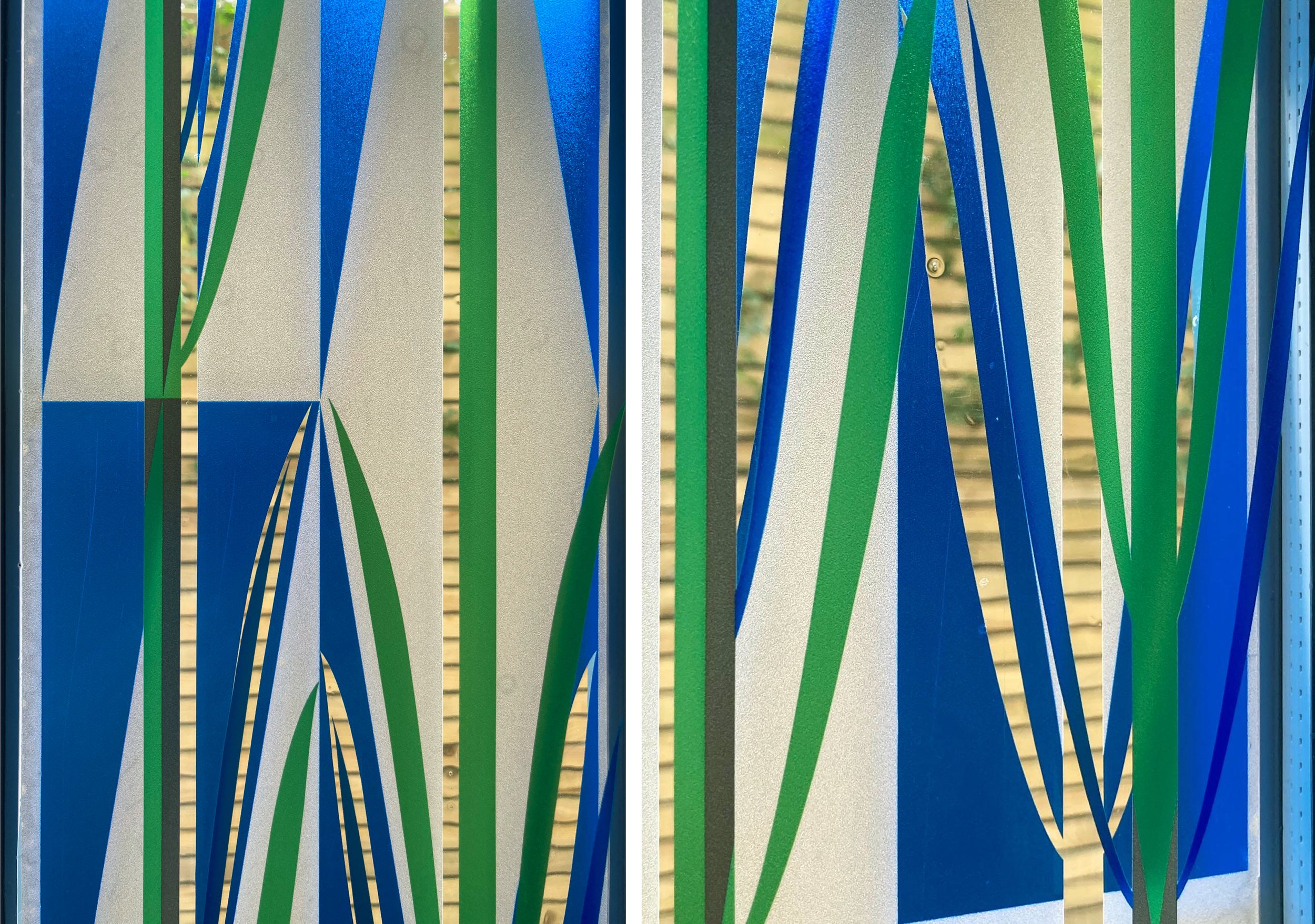

Invitation to our studio from 2010 (left) and 2021 (right).

Night time photo of the studio, with Ray’s work upstairs and mine downstairs.

Open studio weekend has been and gone - the first since 2010 and therefore the first thorough tidy up in eleven years as we showed our studio and its contents to friends, family and neighbours. Luckily they came, bought things and we all enjoyed ourselves in a restrained semi pandemic sort of way. Warm autumn weather meant the garden was looking good (below).

Back of studio from the garden.

Studio windows from the inside, top Ray’s, bottom mine.

Paintings and piles of drawings in Ray’s studio..

Morning sunshine through stained glass in my studio.

As well as a tidy up, the weekend prompted me to make a display of my work in the windows and work out what I wanted to say about it. Of course I’d rather say nothing at all, but that doesn’t get you anywhere. I’ve also put up a couple of displays on the wall which I think will stay there for a while, one is a map of the UK marked with the location and photos of ten commissions from 2008 - 2019, the other is a group of old photos of me at work on commissions from 1990 - 2014 (below left and right). For anyone who hasn’t visited our studio, I hope you enjoy looking at the photos of it, and please feel free to make an appointment to visit while there is work out to see.

Wall displays of commissions and photographs.