Inside the short course top workshop at West Dean College, February 2022

Cutting out a circle, working out how to lead inside it, and the offcuts from several attempts at circle cutting.

On the last occasion I wrote about West Dean students’ work I was inspired by the glass painting they did. On this course it was the adventurous cutting and leading stages of making a stained glass window that stood out. The trail blazer was a student (who specialised in metal restoration) who was determined to cut a hole out of a piece of glass (above); as a beginner this took him several attempts. The finished piece was fun, but what I really liked was the panel made from offcuts, where he had to match complicated shapes and then work out how to feed the lead around them (below).

Panel made from the circle offcuts.

Simple colour, cutting and leading.

Another student, also a beginner, made a window that was lovely and simple, with a few lead lines and a few painted ones to make a fanlight that was really effective (above). Some more interesting leading, or rather copper foiling, was the result of a thermal crack when quite a large piece of enamelled glass was fired in a cold spot in the kiln (below).

Thermal crack, made into a panel.

Three from a series of seven panels by a more experienced student.

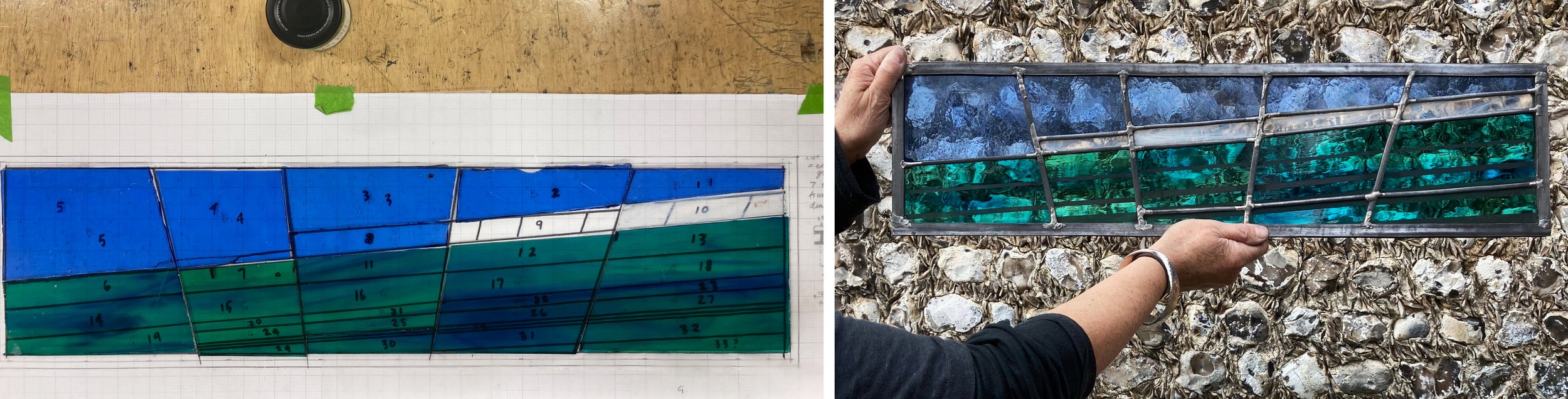

Another student made a series of panels with sharp graphic lines, painting and sandblasting. The smaller ones (above right) were based on letters of the alphabet. For a returning student I devised a challenge using four pieces of painted enamelled glass and just three other colours that pushed her use of glass by making her play with the material, cutting and designing as she went along (below).

Composition challenge in progress.

This was a very companionable course, and as you can see the work produced was diverse, interesting and unexpected. I’m teaching again for a week in July, here is a link if you would like to sign up, West Dean College is a great place to stay and study.

Students cementing their panels on the final morning.